"Adjacent Titles" that Get Autism Right

If you are any part of the children's literature community, you've heard the conversations currently being had about under various hashtags: most visibly, #weneeddiversebooks and #ownvoices. For the non-initiated, these hashtags represent two, shall we say, movements, in the kidlit world -- both long overdue. The publishing world has been extraordinarily slow to respond to calls for more representation, more diversity, and more people telling their own stories. So even though these are difficult, nuanced, sometimes upsetting conversations, most of us agree that it's about time.

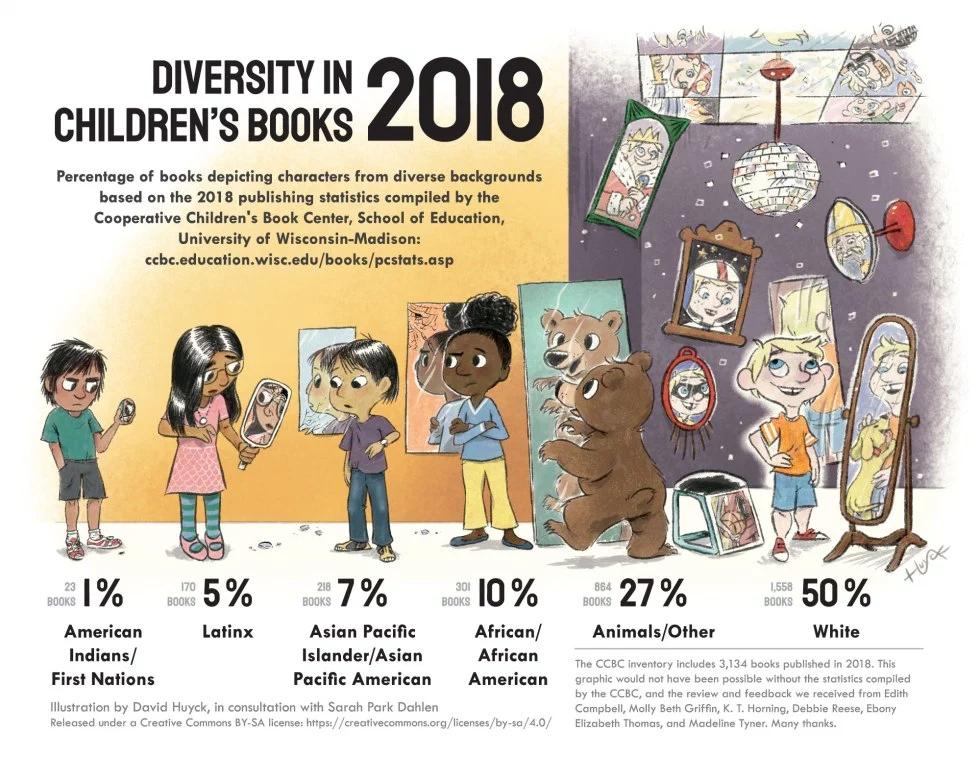

If you think I'm exaggerating, about the lack of diversity in children's literature, take a look at this graphic produced by the Cooperative Children's Book Center reflecting representation of depictions of race in children's lit:

If you want to read more about the ongoing discussion, look here (this one is over 20 years old, and more relevant than ever) or here or here, or listen to author Kekla Magoon discuss it clearly in this podcast episode from author Grace Lin's excellent podcast, Kidlit Women.

The discussion and belated addressing of the problem is great, but it's also controversial. Some writers feel they are being censored, or that they can't write right now if they are white. Some people think it's too late. And some, many, are celebrating. Questions like:

What happens to writers who don't belong to under-represented or marginalized groups? Does this mean people "without hashtags" can't get published right now? Is there enough room on the bookshelves for everyone?

My own work thus far includes characters grappling with elements of mental health, because that's what I know about: anxiety, OCD, Tourette's, depressions, ADHD, and autism. This is the kind of diversity that I feel "qualified" to write about. And yet: I'm not the one who is dealing with all of the above: my kids are.

So, it's not OWN VOICES exactly.... right?

It's, what? ADJACENT VOICES?

So, are adjacent voices welcomed into the conversation? My fear: what if, despite my knowledge and good intentions, my stories actually speak for other people and I'm one of the ones holding back change?

This is the question that has plagued me as a writer, particularly as my own young adult novel featuring mental illness and a character with Asperger's is making its rounds throughout publishing houses as I write.

Can I write about these issues? Am I the right person to tell this story?

Or, should I "step aside," as Kekla Magoon requests of white writers writing about issues of race? Do the same rules apply when writing about disability and mental health as they do for issues of race and culture? Does being adjacent to an under-represented group give me the knowledge and experience to depict the experience with empathy, accuracy, and grace?

I wish I knew the answer.

Instead of debating, though, I thought I'd point out a few books I've read that, IMHO, get it right. And trust me, getting it right isn't easy.

![A Boy Called Bat by [Arnold, Elana K.]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51tsXTT0NNL.jpg)

Elana K. Arnold and Charles Santoso's A BOY CALLED BAT:

As far as I know, author Elana K. Arnold is neither autistic nor has an autistic child or close family member (I could be wrong -- but it's not mentioned anywhere that I could find), and yet she sensitively and lovingly tells the story of Bixby Alexander Tam's character growth over three books as he cares for his pet skunk Thor, navigates new friendships, deals with change, and learns, finally, to say goodbye.

From my review of the third installment, BAT AND THE END OF EVERYTHING: Arnold expertly conveys the sometimes-too-literal but always thoughtful interior thoughts of a child on the autism spectrum, though Bat’s fear of change and uncertainty will resonate for every reader.

![Bat and the End of Everything by [Arnold, Elana K.]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/41odWFjiuhL.jpg)

What Arnold does best is to show how Bat feels, and how hard it sometimes is for him to convey those feelings to others. My own teenager, who has Asperger's, identifies with Bat's innermost thoughts, as well as his frustration when others don't "get" him. In fact, he asked, "how did the author know?" Arnold portrays a character with autism who deals with everything neuro-typical children deal with (well, if they had a pet skunk, that is) without making the story about an autistic child. It's just a story about a boy named Bat.

Honest, warm, and real, in A Boy Called Bat and its sequels, Arnold richly develops characters who grow and change with time. I particularly love Bat's relationship with his older sister Janie. Like older sisters everywhere, she both loves her brother and and is often exasperated with him. But it's not because of his autism - it's because that is how big sisters feel.

So it's possible to write "outside your lane," as they say, and do it well. I have three books (and more where that came from) to prove it.

It is possible to create characters with diversity without claiming a book as #ownvoices. But if you do this as a writer, be prepared for some backlash, and do your research. Be sure that like Arnold, you get it right. Not just because that is what people are looking for right now, but because getting it right matters to the readers who deserve to see accurate and nuanced portrayals of all kinds of diversity.

So I still don't have the answers. But I love thinking about the possibilites.

Weigh in! Join the conversation.

(You might need a cocktail first.)